Corpus Christi Year B

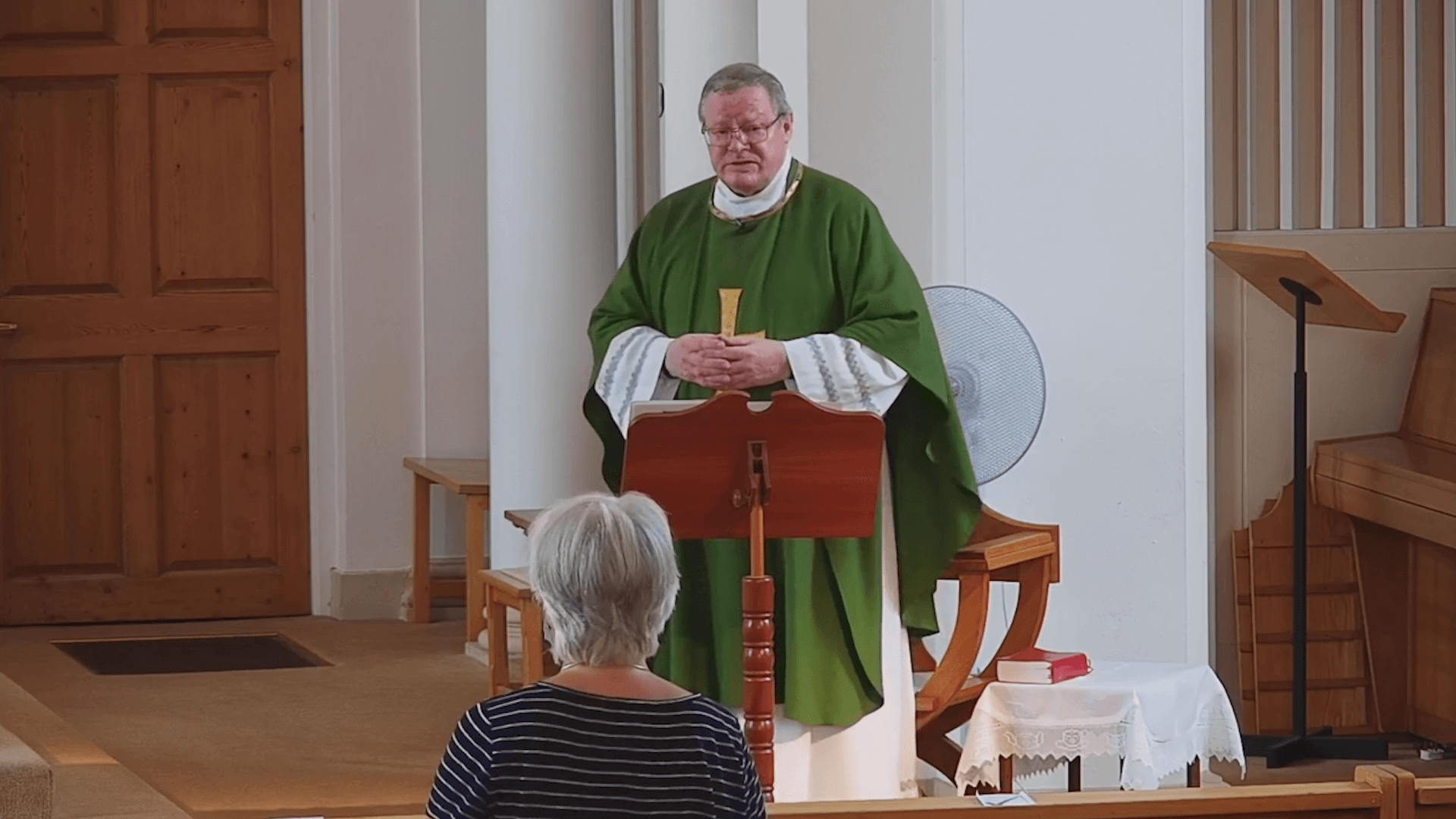

Sometimes we find ourselves in a queue with a bunch of strangers, shuffling down the aisle in church, and we forget that we are standing with our families on the pathway to heaven about to partake of the Body and Blood of Christ offered once for all time for the salvation of the world. Perhaps we have all walked down that aisle together? The sacrificial nature of the Eucharist is clear from Jesus’ words and the actions at the Last Supper, but hearing the words of institution over and over can become a rote behaviour that obscures their lifegiving meaning. In the words of Mark’s gospel, “While they were eating, he took bread, said the blessing, broke it, gave it to them, and said, “Take it; this is my body.’ Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed for many.’ The primary sacrificial context for the Last Supper comes from the Passover feast in which the meal is situated, but the offering of Jesus’ Body and Blood on behalf of ‘many’ - that is, for all people - takes on and reinterprets much more of the sacrificial imagery of the Old Testament. The bread that he broke is a sign of his body, which he will offer in death, the true bread of the presence. The “blood of the covenant” shares in the imagery of the ceremony in Exodus in which Moses sprinkled blood on the people of Israel as a sign of their obedience to the covenant. The phrase “shed for many” draws us inexorably to the Suffering Servant of Isaiah, who pours himself out as an expiation for the sins of the people. These sacrificial realities are not alien to the Last Supper. They are an inherent part of Jesus’ actions, which he interprets for his apostles prior to the crucifixion. But for these understandings to come to the fore, the first Christians had to meditate and reflect on what Jesus had done and what this meant for the continuing life of the church. The author of the Letter to the Hebrews makes it his mission to explicate and explain what took place on Calvary in the light of the Jewish sacrificial system. He explains that Jesus is not only the sacrifice for the sins of the world but also the perfect high priest and that through the offering of himself as the perfect sacrifice, Jesus “is mediator of a new covenant: . . . Those who are called may receive the promised eternal inheritance.” Jesus’ words over the bread and wine, then sharing it with his disciples, signifies his giving them a share in the atoning power of his death. And that atoning power has as its goal eternal life with Jesus. But it was not just those who sat at the table with Jesus who are able to share in the atoning power of Jesus’ sacrifice; Jesus opened the way for all to share in the eternal inheritance.